Overgrowth

Philadelphia’s Rail Park and a neighborhood in transition.

Spring 2018 | By Maggie Loesch

I. Blight & Decay

Play audio as you begin reading.

Where trains once rushed above an industrial Philadelphia neighborhood, there are now decaying tracks overgrown with weeds. On the western spur of the deteriorating Reading Viaduct, the barren land is being transformed for a better purpose.

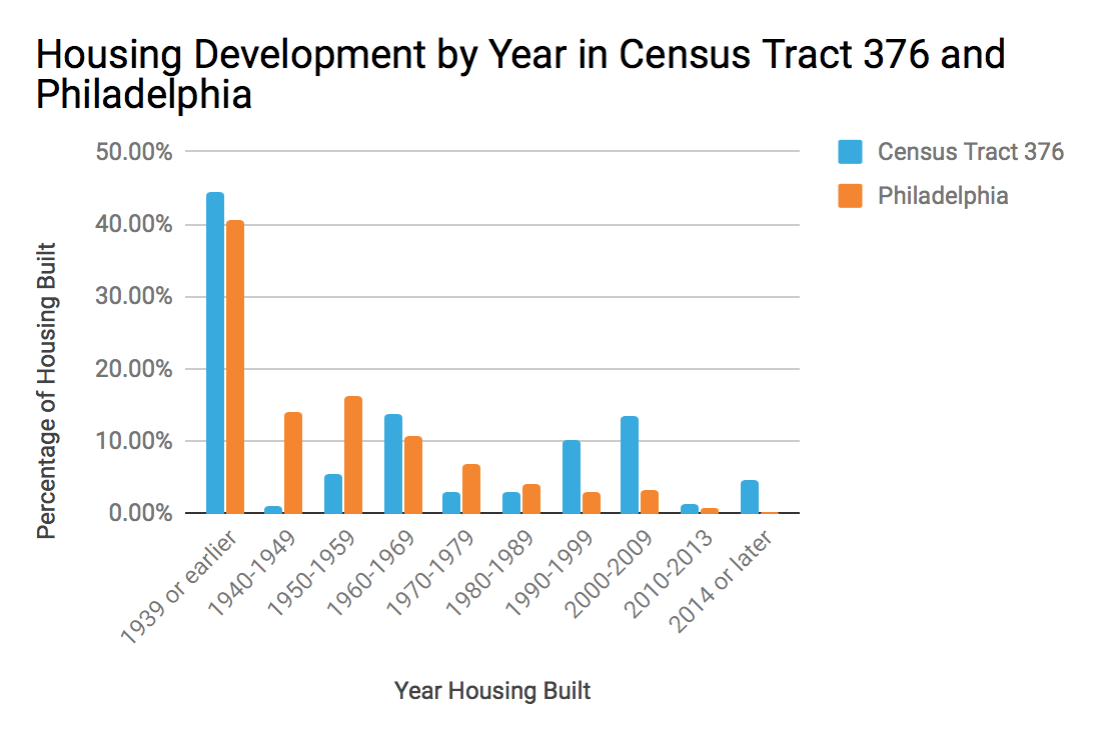

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, factory and railroad workers lived in the neighborhood near their jobs, and passenger and freight trains utilized the tracks that criss-cross 13 feet above the streets.

The Reading Viaduct will soon become a park, the latest in a recent trend of rails-to-trails redevelopment projects taking off around the country. Turning unused train track infrastructure into neighborhood green space creates economic, environmental, and social benefits. But it is a lengthy process which requires robust community support.

The viaduct cuts through the Callowhill neighborhood, which sits in the northeast corner of Center City. The area stretches from Broad to 8th, between the Vine Street Expressway and Spring Garden Street, and was historically a manufacturing district linked to the rest of the region by railroads.

In the 1930s, the Great Depression gripped the nation, and industry in Philadelphia suffered as a result. Afterwards, the manufacturing epicenter recovered slightly before experiencing another setback in the 1950s and ‘60s. Outsourced labor and affluent people leaving cities for the suburbs led to population loss and a lower tax base, which resulted in neighborhood disinvestment, according to Dr. Jeffrey Doshna, a professor of City, Transportation, and Regional Planning at Temple University, who specializes in urban redevelopment.

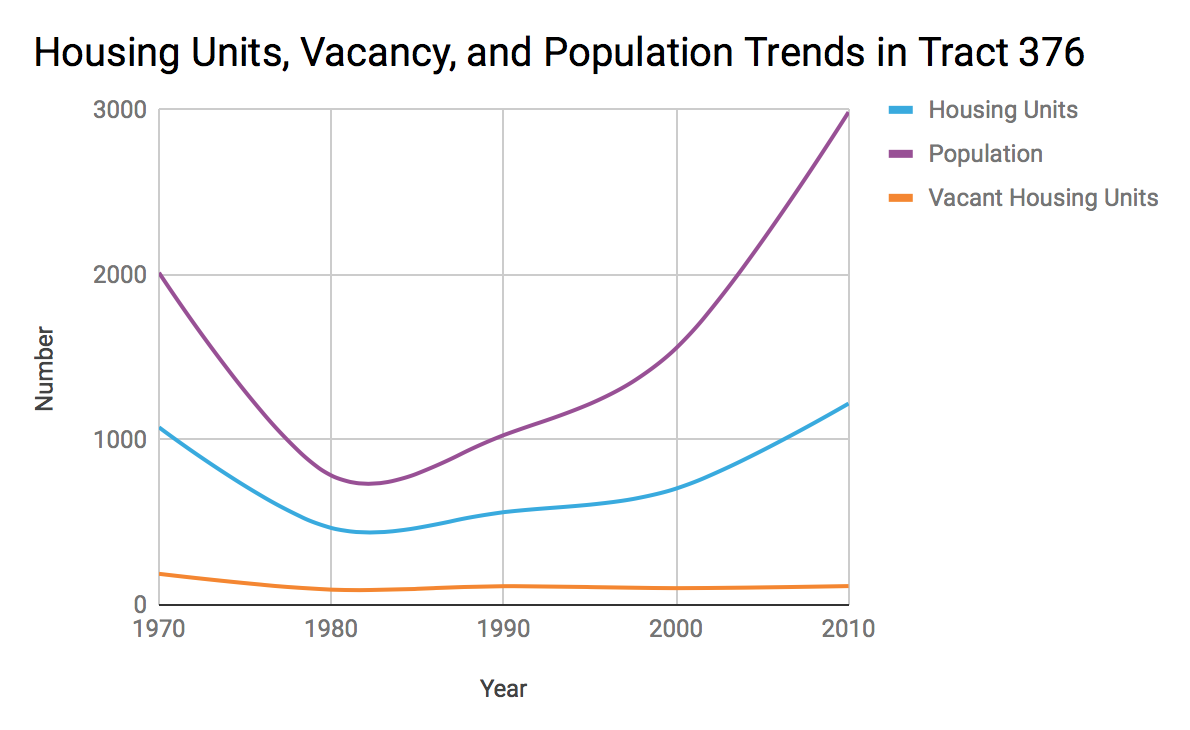

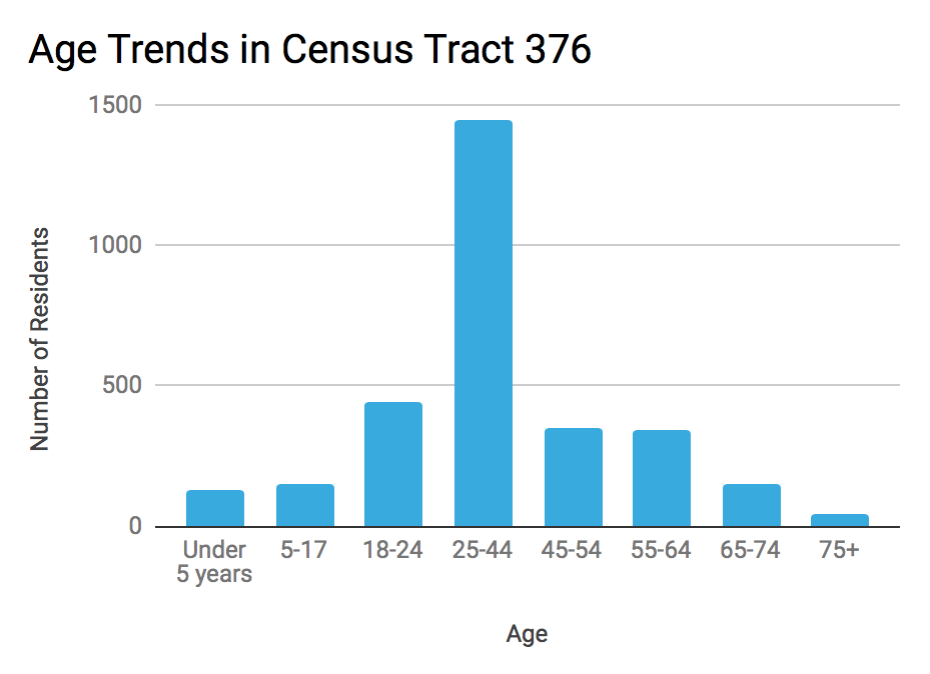

The area has redeveloped slowly since 1990, with population and housing units increasing more and more each decade. As residential life came back the area, support grew behind the idea of turning the viaduct into a community asset.

Neighborhood parks increase residents’ property values, quality of life, and sense of community, and even health outcomes, said Doshna.

Creating parks from former railways proved effective with projects like New York City’s High Line and Chicago’s 606 Trail, which both serve as tourist destinations and multi-use paths.

In a neighborhood with almost no green space, this development will serve as a local resource and drive economic investment in the neighborhood from visitors, Doshna said.

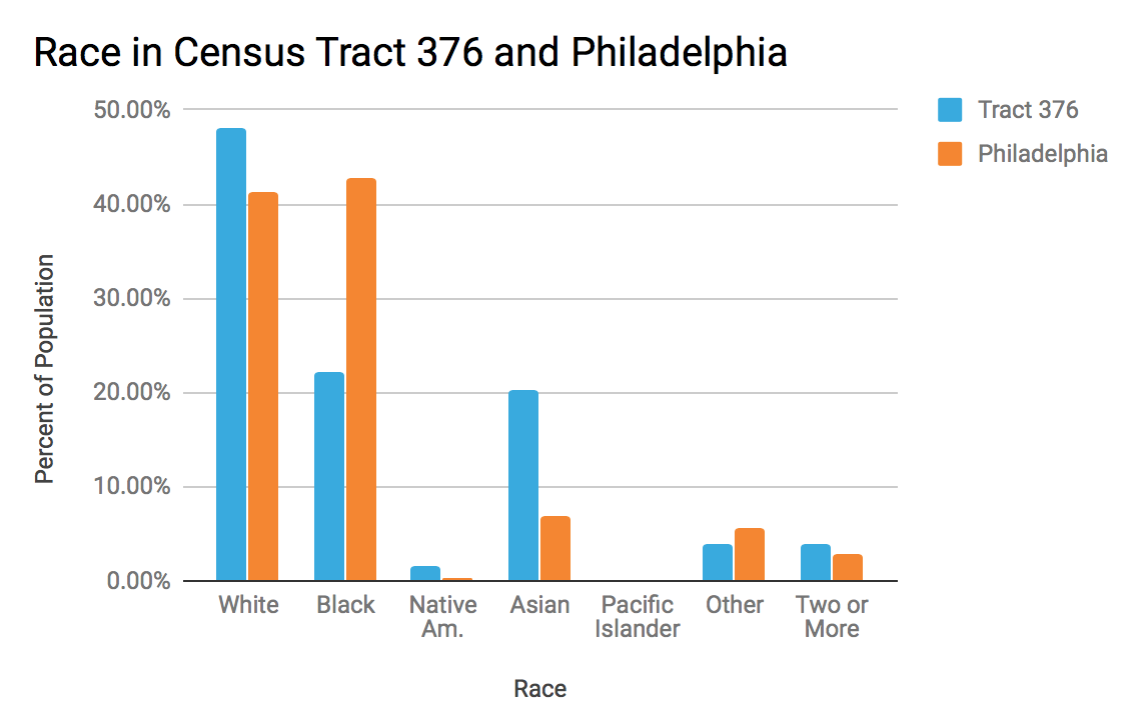

In the gentrifying district, residents and developers often cite the diversity of people and industries as a highlight. “It’s very interesting little pocket of a lot of different things going on,” said long-term resident and activist Sarah McEneaney.

The Rail Park fits in with eclectic aesthetic of the neighborhood.

Play audio and scroll through slideshow below.

II. Rails to Trails

Long time residents like McEneaney have been forces for change in the near 20-year fight to create the city’s first elevated rails-to-trails redevelopment.

The story of her involvement dates back to the community coming together to fight against the city’s plans to build a baseball stadium in Chinatown in 2000. She realized she had neighbors who wanted to improve the area, and “the neighborhood association came directly out of that, and then you could say that founding Reading Viaduct Project (RVP) grew out of [the Callowhill Neighborhood Association],” said McEneaney.

Since 2003, RVP wanted to turn the three-quarters-of-a-mile worth of elevated viaduct into a neighborhood green space.

Play audio and scroll through slideshow below.

The organization partnered with Center City District, the local business improvement district, in 2009 to raise funds and get closer to making their dreams into a reality.

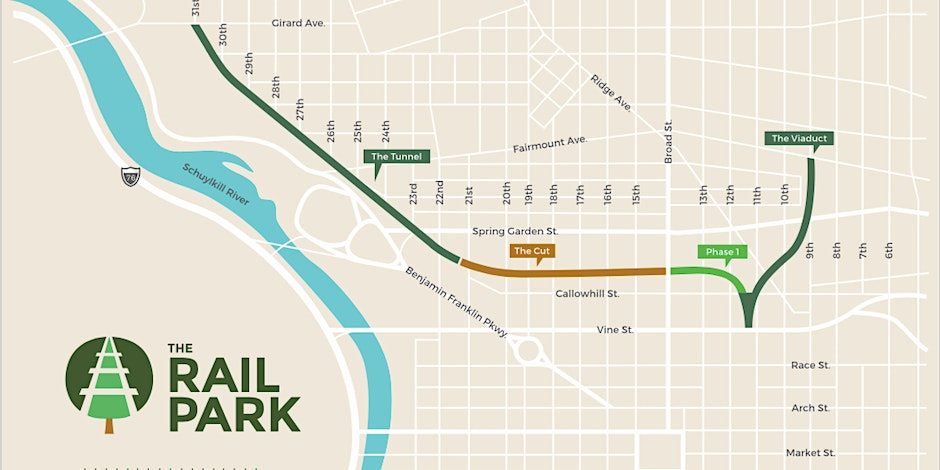

While RVP focused on how to turn the viaduct into a park, another group was looking for a larger goal. Friends of the Rail Park, founded in 2010, intended to reuse a whole network of Philadelphia’s defunct rail infrastructure. It sweeps through the north side of Center City and totals three miles, including above ground and underground sections deemed The Viaduct, The Tunnel, and The Cut.

The two groups joined forces in 2013 and have worked towards their common goal since. The process has involved hanging flyers, hosting community meetings, talking with neighborhood organizations, and obtaining the ever-elusive necessity— funding.

The costs of demolition and rebuilding from scratch would far outweigh those of clearing vegetation, laying down paths, installing landscaping and benches, and park maintenance. A quarter mile of green redevelopment will cost almost $10 million, so it can be estimated that the entire three-mile project will come in around $120 million.

Although transforming the space isn’t cheap, demolishing it would cost even more. “There’s been a number of studies done by the city,” said McEneaney, “and it’s always cheaper to remediate it into a park.”

“We factored in some of the environmental benefits from having green space compared to pervious surface or just regular development, and then social benefits as well,” said Tanner Adamson, who completed a community analysis of the project for his Master of City, Transportation, and Regional Planning degree in 2016. When people are around green space, they also experience lower rates of asthma and stress.

After years of fundraising, the group cobbled together $9.6 million from individual donors, the City, and the William Penn Foundation, among others. Friends of the Rail Park broke ground on what they appropriately termed “Phase One” in 2017, which is set to open in June 2018.

The quarter-mile stretch of park once joined the train line from the west side of the city with the Reading Railroad. Beginning at Broad and Noble Street, the viaduct curves southwest to Vine and 11th Street. It was purchased by SEPTA after the last train ran on it in 1992, and was sold to Friends of the Rail Park a few years ago.

The first section of the park will feature a boardwalk path, landscape planters, and wooden swings; it will also serve as a community gathering space. Drawing residents out into shared spaces is an integral part of creating a sense of connection and belonging in one’s community, according to Doshna.

III. Regrowth

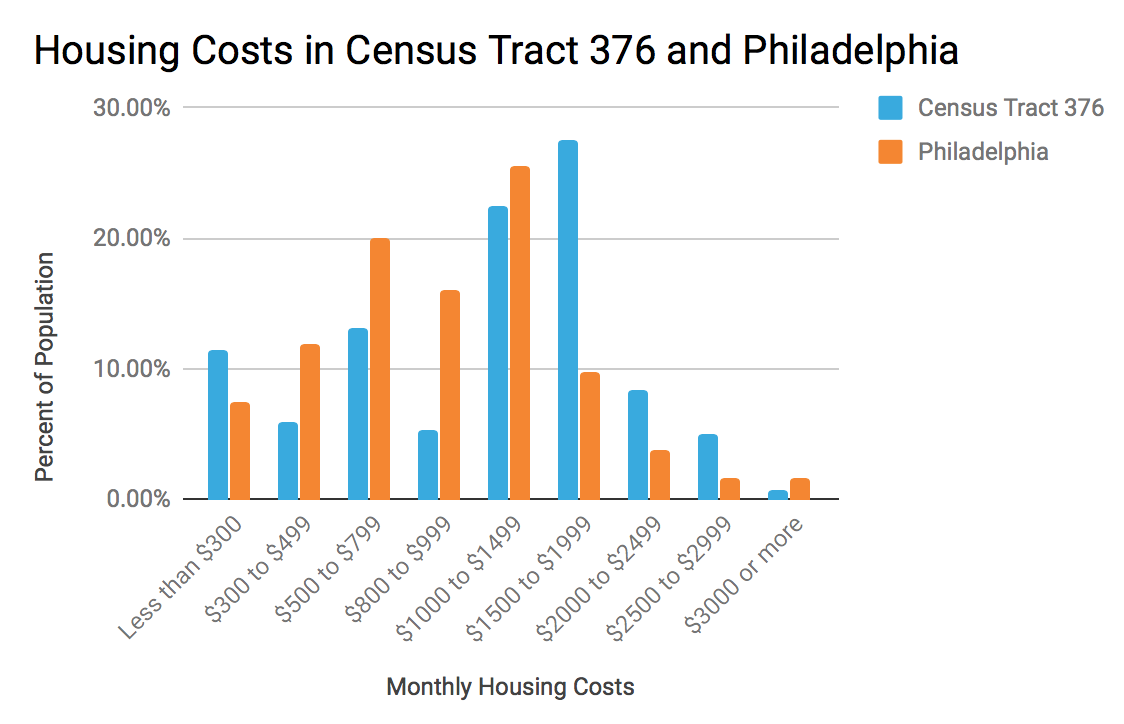

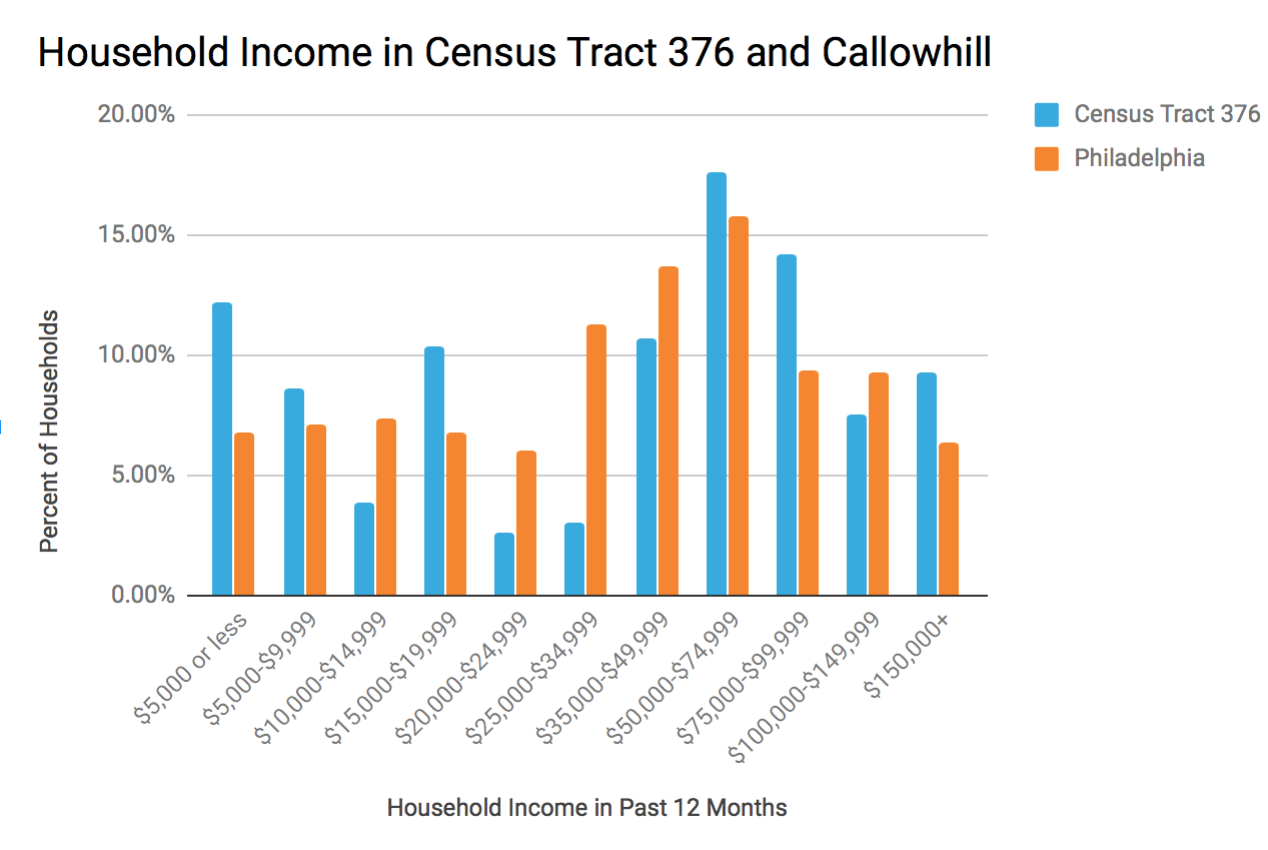

A park will also further increase property values and development in the neighborhood, which has been gentrifying for the past 20 years. Data from the U.S. Census shows that the population here has increased faster than the number of housing units, and this increased demand leads to rising rents and property taxes. An urban planning concept called the Proximity Principle acknowledges people will shell out more money to be closer to parks; this means home values in the area will see another bump upwards.

Developers in Callowhill, such as Post Brothers, who owns the Goldtex Building at 12th and Wood Street, have invested in the area specifically because of the development of The Rail Park. Post Brothers has been the single largest contributor to the park’s development, according to Jonathan Coyle, property manager at the building.

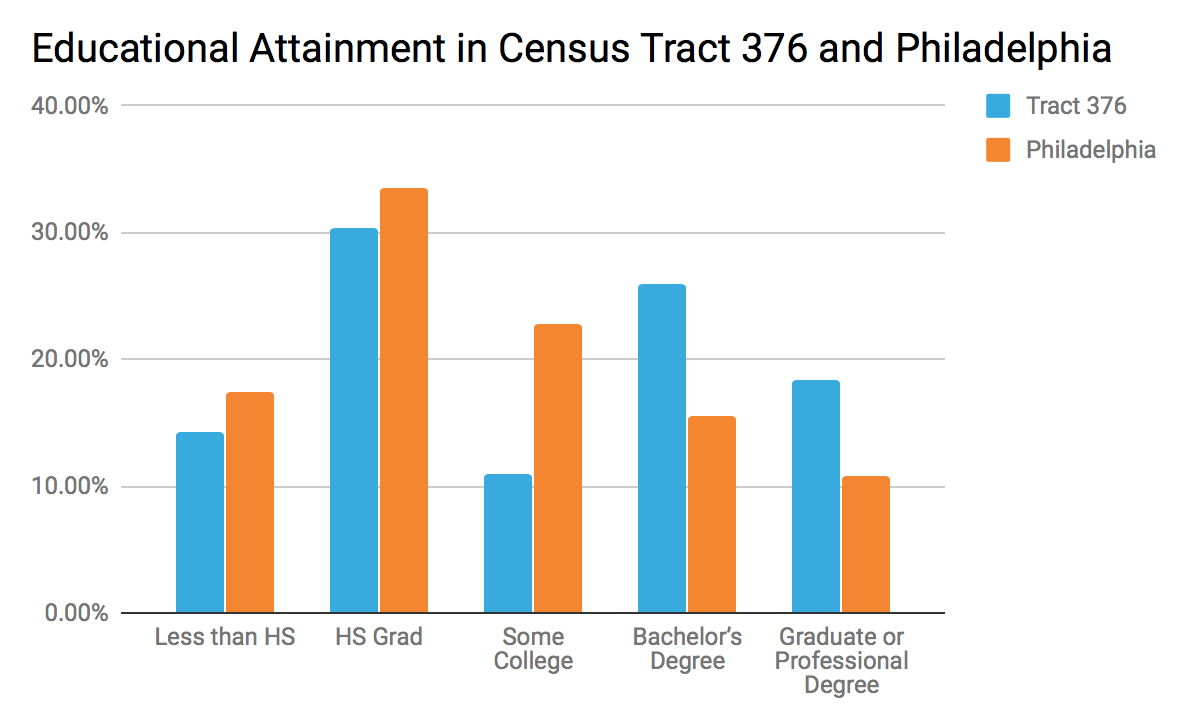

Gentrification is often painted as affluent, white residents moving into historically black neighborhoods and taking them over. In Callowhill in particular, “there’s going to be an uptick probably in property values around it, but property values in that neighborhood were very low to begin with,” said Doshna, “so some some increase in value some reinvestment in the neighborhood is good.”

Residents in the area are in favor of development as well. “I’m glad they’re doing something in this city,” said Leonard Mason, 56. The Baltimore native is staying at Our Brother’s Place, a local homeless shelter. “You can buy [property] now, it’ll be worth that much more. They’ll put in lights. We will be safer: me, and you, and everybody else.”

According to Doshna, displacement affects primarily renters who cannot reap the benefits of increased property values. People in this demographic are the ones typically negatively impacted by gentrification.

Neighborhood groups such as the Philadelphia Chinatown Development Corporation are concerned about equitable development in the area.

“PCDC in the beginning was quite vocal against [The Rail Park], and they wanted to tear down the viaduct because they said they wanted to have land for affordable housing,” said McEneaney.

Other cities with similar projects, such as The 606 Trail in Chicago, have experienced surges of change in neighborhoods surrounding newly built parks.

“The biggest challenge we face is that we’re linked to the potential for gentrification and displacement,” said Caroline O’Boyle, The Trust for Public Land’s Director of Programs and Partnerships for The 606. “It’s really important to figure out what the long-term strategies are for maintaining the ability of the current residents to be able to stay and enjoy the asset you’re building.”

In terms of solutions, O’Boyle suggests programming that helps tenants achieve homeownership, as well as zoning restrictions. Philadelphia currently has policies in place that give developers bonuses to build higher than zoning permits if they provide affordable units or contribute to the Housing Trust Fund, which provides repair assistance and construction of new homes to Philadelphians living in poverty.

Currently in the works are City Council bills mandating developers build affordable housing in new developments. Councilwoman Maria Quinones Sanchez champions such bills as a response to neighborhoods like Fishtown’s rapid gentrification.

The Callowhill neighborhood has been redeveloping for the past two decades, and more development to come is not something that can be pinned solely on The Rail Park. As their process continues, Friends of the Rail Park is set on having conversations with the communities it strives to serve, McEneaney said.

She described engagement as their “biggest challenge and most important work.”

Turning an eyesore into a productive space that adds social, economic, and environmental value to the neighborhood is no simple feat; planning, funding, and executing the project are only the beginning of the deep considerations necessary by residents about how they would like to see their community evolve in the future.